“Portraits of the Passion: The Crucifixion”

Matthew 27:33-44

Pastor Kevin Vogts

Trinity Lutheran Church

Paola, Kansas

Lent Service IV—March 18, 2020

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Our Lenten sermon series this year is “Portraits of the Passion,” the

Lenten story illustrated with slides of artworks from the Nelson-Atkins Museum

and Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas.

“Pax with the Crucifixion”

French – c. 1550 – Enamel with Gilt Bronze Frame

Among the artworks on display in these museums, the one image that you

will find more often than any other is “The Crucifixion.” And, indeed, art

historians will tell you that among all the artworks ever created in the entire

history of the whole world, “The Crucifixion” of Jesus Christ is the one image

that has been portrayed far more often than any other.

The question is: Why? His crucifixion does not stand out because

crucifixions were rare in the ancient world. Hundreds of thousands of

other people besides Jesus of Nazareth were crucified by the Romans and other

ancient empires. And, doesn’t a crucifixion seem like an awfully odd image

to become humanity’s all-time favorite anyway? It is, after all, nothing

other than the most brutal form of execution ever devised by wicked humankind.

So, why has this one particular crucifixion, of Jesus of Nazareth, become so

revered by us?

Peter explains the unique significance of this particular crucifixion:

“He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross.” Paul says, “God

presented him as a sacrifice of atonement, through faith in his blood.”

At the place in Jerusalem where tradition says Christ was crucified,

which is now inside a chapel, there is an inscription in the floor: “This Is the

Center of the Universe.” It is 40 years ago this year that I stood in that

chapel on Good Friday, and reading that mystical inscription brought tears to my

eyes. For, it is so true that what happened on Mt. Calvary is the central

event in the history, not just of Christianity or western civilization, but the

central event of the history of the whole world, yes the whole universe.

By his death on that cross that day, God’s own Son sacrificed himself to pay for

the sins of all humanity, including your sins and mine. Because of his

sacrifice, your sins are all forgiven, you are at peace with God through his

blood, shed on the cross.

This exquisite French enamel plaque from the 1500’s on display at the

Spencer Museum is actually only about three inches square. You may have

been to churches were the minister and people exchange a kiss of peace, often

substituted with a handshake, before receiving Holy Communion. You may

have also heard in the news lately that because of the current virus outbreak

many churches have temporarily discontinued this practice or substituted

something like an elbow bump.

The outbreak we are currently enduring is certainly something none of

us has ever experienced before, but actually it’s not unprecedented in the

history of the world. For, during the Middle Ages this enamel plaque was

their substitute for the kiss of peace when plagues ravaged Europe. It is called

a Pax, the Latin word for peace. Rather than “passing the peace” by

kissing each other, the minister and congregation would exchange their kiss of

peace by passing around and all kissing this plaque. You see, they knew

enough not to pass on the plague by kissing each other, but they didn’t

understand germ transmission, and realize that having everyone pass around and

kiss this plaque instead was just as bad or worse.*

Standing next to the cross are Jesus’ mother, Mary, and the Apostle

John. In a very personal passage in his Gospel, John himself remembers how

from the cross Jesus committed his mother Mary into John’s care: “Near the cross

of Jesus stood his mother . . . When Jesus saw his mother there, and the

disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, behold

your son,’ and to the disciple, ‘Behold your mother.’ From that time on, this

disciple took her into his home.”

Above Christ is a placard with the letters “INRI.” After a person

was condemned to be crucified, a placard like this, called a “titulus,” would be

prepared stating the crime for which he was being executed. Mark describes

it as, “The written notice of the charge against him.” It would be carried

before the condemned man as he was paraded out carrying his cross to the place

of execution and then be posted there, as a warning to all not to commit this

same crime.

John reports, “Pilate had a notice prepared and fastened to the cross.

It read: JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS. Many of the Jews read

this sign, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city, and the

sign was written in Aramaic, Latin and Greek.” Matthew says, “Above his

head they placed the written charge against him.”

“INRI” are the initials for the Latin phrase, “Iesus Nazeranus Rex

Iudiorum,” “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.” This was the

official charge against him. His false accusers had said, “Anyone who

claims to be a king opposes Caesar,” and although Jesus explained to Pilate, “My

kingdom is not of this world,” he was officially—although wrongly—executed for

rebellion against the Roman Empire.

Psalm 22 which we read earlier prophesied, “They have pierced my hands

and my feet.” We see in this beautiful enamel blood spurting forth from

the five wounds of Christ, where his hands and feet were nailed to the cross,

and his side where he was pierced after his death. As “doubting” Thomas

said, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the

nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it.”

“Triptych with the

Crucifixion and Four Saints”

Bologna, Italy – 1400’s – Ivory with Traces of Polychrome & Gilding

This Italian Ivory triptych from the 1400’s is also

very small, about foot tall. The side panels with four saints fold in, and

it was designed to be a portable shrine for use in private devotions.

In this triptych there is something very surprising, and at first

glance rather bizarre, perched on top of the cross. A pelican has built a nest

there, and is feeding her young. What in the world could THAT mean?

A pelican feeding her young is actually an ancient Christian symbol, called “The

Pelican in Her Piety.” It is based on the fact that a pelican, if

necessary, will pluck open her breast to feed her young with her own blood.

In the same way, our Savior shed his own blood to give us eternal life, and he

feeds with his own body and blood in the Sacrament of Holy Communion.

I have to think about the person 500 years ago who used this triptych

for private devotions, whom I’m sure understood the unusual symbolism of “The

Pelican in Her Piety” atop the cross. Maybe that person requested this as

part the triptych, perhaps it was one of his or her favorite symbols.

“Crucifixion”

Johann Martin Kremser-Schmidt – c. 1797 – Oil on Canvas

This Austrian oil painting from about 1800 is very dark, reflecting the

extraordinary darkness that veiled the world as Christ hung on the cross from

noon to 3:00pm, as Mark reports, “At the sixth hour darkness came over the whole

land until the ninth hour.” Jesus is crucified between two criminals, as

Luke reports, “When they came to the place called the Skull, there they

crucified him, along with the criminals—one on his right, the other on his

left.”

The heartless soldiers are portrayed shamefully playing dice while the

Son of God suffers and dies for the sins of the world. They are really

symbolic of the shameful preoccupation of all mankind with wicked pursuits

instead of the Lord’s will.

As in many portrayals of the crucifixion, there is a skull at the base

of the cross. The reflects the name of the place of crucifixion,

“Golgotha” or “Calvary,” which mean “The Place of the Skull.” But, the

skull at the base of the cross also symbolizes that by the cross Christ

triumphed over death for you and all who trust in him. As Paul says, “Our

Savior Jesus Christ has abolished death and brought life and immortality to

light through the gospel. . . The last enemy to be destroyed is death.”

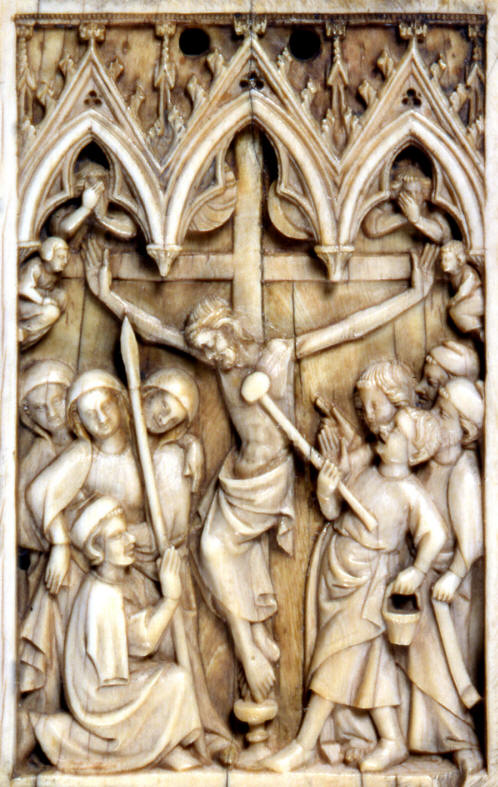

“Plaque with the Crucifixion”

French – 1300’s – Ivory

This French Ivory plaque from the 1300’s is about eight inches tall.

It was once part of a diptych, two panels that would fold together, and was also

used for private devotions.

At the base of the cross in many of these artworks are two groups: The

soldiers who crucified Jesus; and his mother along with his closest female

followers, as Mark notes, “Many women were there, watching from a distance. They

had followed Jesus from Galilee to care for his needs.”

The stick and bucket held by one of the soldiers reflects John’s

report, “Jesus said, ‘I thirst.’ A jar of wine vinegar was there, so they

soaked a sponge in it, put the sponge on a stalk of the hyssop plant, and lifted

it to Jesus’ lips.” A poignant imagery in this plaque, that is found in

many classic portrayals of the crucifixion, is angels who are hiding their faces

from the horrible sight of their Lord being crucified.

“Crucifixion”

Hans von Aachen – c. 1575 – Gilt Bronze

John reports, “The soldiers came and broke the legs of the first man

who had been crucified with Jesus, and then those of the other.” It was

common to break the legs of crucifixion victims in order to hasten their deaths.

In this German gilded bronze plaque from the 1500’s the two thieves on either

side of Jesus have had their legs broken.

John continues, “But when they came to Jesus and found that he was

already dead, they did not break his legs. Instead, one of the soldiers

pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water.”

Modern medical doctors interpret this to mean that Jesus probably died as a

result of congestive heart failure, a buildup of fluids around the heart.

Quoting the Old Testament, John says, “These things happened so that the

scripture would be fulfilled: ‘Not one of his bones will be broken,’ and, as

another scripture says, ‘They will look on the one they have pierced.’”

“The Crucifixion”

French – 1470 – Stained Glass

Probably the most common medium for Christian artwork, still today, is

windows made of stained glass. It was during the Middle Ages that stained glass

was invented, as in this French example from the 1400’s on display at the

Nelson-Atkins Museum.

The hymn “How Great Thou Art” expresses the significance of “The

Crucifixion”:

But when I think that God, His Son not sparing,

Sent Him to die, I scarce can take it in,

That on the cross my burden gladly bearing

He bled and died to take away my sin.

Return to Top | Return to Sermons | Home | Email Church Office